Champ Man 03/04, the ‘Diablo’ tactic & when Frank Lampard made it real

On Championship Manager 03/04 there was an extremely successful tactic that turned out to be a bug in the game. Then a few years later Frank Lampard went and turned it into real life for Chelsea.

You might not play it anymore, but virtually anyone with an interest in football has delved into the world of Championship Manager or Football Manager at some point.

The management simulator is played (and written about) by adults who should probably know better, and the growth of mega-money games like FIFA has had little impact on its popularity.

There are many reasons to love CM/FM, but perhaps the game’s biggest draw over the years has been its staunch commitment to realism.

From youth team training to the minutiae of contract negotiations, the game has always done its best to imitate real life — often at the expense of ‘fun’ in the conventional sense.

Once, however, it failed to do so.

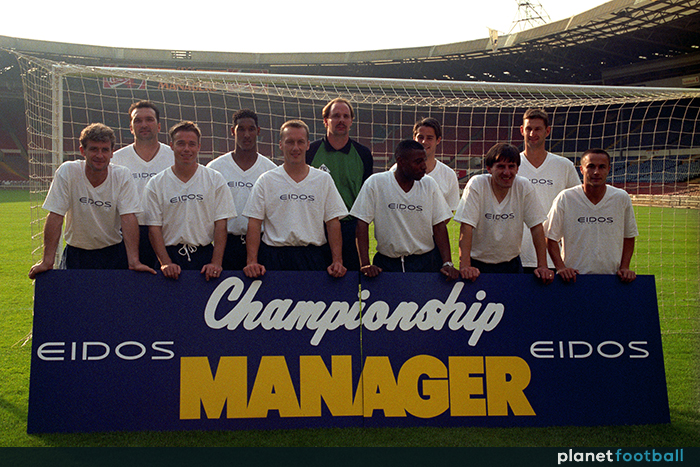

Championship Manager 03/04 was significant for two reasons. First and foremost, the game was a swansong for the original series, the last CM developed by Sports Interactive and published by Eidos.

The breakup of those companies marked a schism in CM history.

After 03/04, Eidos kept the Championship Manager name but delivered a succession of games filled with bugs. Sports Interactive adopted the new Football Manager title, but its game was much truer to the original series.

Football Manager, confusingly, became the *real* Championship Manager.

But CM 03/04 was significant in another way too. Significant because it delivered, wholly by accident, CM’s first ‘cheat’, a quirk of the match engine that allowed one tactic to run riot over all others.

The ‘Diablo’ tactic

That tactic was the infamous ‘Diablo’, a wide 4-1-3-2 that, for one reason or another, produced a silly number of goals. A really silly number.

First shared online by a gamer named ‘El Rosso Diablo’, the tactic was built around a free-roaming central midfielder with a ‘forward arrow’ right up to the central striker position.

That midfielder, who mysteriously never seemed to be marked, would calmly slot home goal after goal from the edge of the box.

The famous Diablo tactic #CM0304 pic.twitter.com/DXIp4WOWaF

— CM_9798 (@CM_9798) December 15, 2017

Looking through some message boards from 2004 reveals how excited gamers were about the tactic.

“I just played one of my personal best matches,” said Anton. “I hammered Valencia 8-1 in the European Super Cup, in wet weather.”

“This tactic is very good!” added Raven. “When I saw Gung Ho I thought ‘Oh shit’, but I tried it and it’s superb. It’s all out attack and good defence at the same time!”

Unfortunately, there was a problem with Diablo. It was too good.

Gamers using the formation soon realised their midfielder wasn’t supposed to score multiple hat-tricks per match, however good his stats were. The tactic wasn’t tactical genius; it was a bug.

Cue the mass stigmatisation of Diablo and its users. Cheating was, after all, incredibly un-CM.

But some refused to jump ship. Anton, our friend who hammered Valencia in wet weather, actually took great care to argue the moral case for Diablo. To the accusation of Diablo being a ‘cheat’, he responded:

“In that case, any tactic that exploits your opponent’s weakness in real life has to be considered cheating too. And don’t tell me that teams in real life don’t use the midfielder who makes penetrating attack runs through the middle.

“Also, many teams in real life use the same tactics: would you consider them to be cheating off of each other?”

And finally, the ultimate challenge:

“All the tactics like Diablo…have been created by understanding how the game works on a computer and in real life… If Diablo is a ‘cheat’ tactic, prove it.”

Vindicating Anton

Unfortunately for Anton, Sports Interactive moved swiftly to prove it. Its next 03/04 update completely neutered the Diablo, teaching the match engine to deal with the forward-running central midfielder.

It wasn’t real. It could never be real.

Those crazy days now seem like a long time ago. While many remember the Diablo fondly — you’ll still find it discussed every now and again on Football Manager forums — most now agree that the ‘tactic’ wasn’t really a tactic in any footballing sense but rather an exploitation of a serious glitch in the CM match engine.

Yet for a few years in Premier League history, one man did his best to prove that the Diablo could have been real.

Did this man, this kind, empathetic man, read those message boards of 2004? Did he see our friend Anton struggling to justify the hours, days, weeks of his life spent plugging away at the Diablo? Did he feel sympathy with the accused manager, forced to prove his integrity to more pious gamers?

I can think of no other reason why Frank Lampard, a midfielder in a Chelsea side littered with goalscoring options, would make it his business to score 20-plus goals in five consecutive seasons between 2005 and 2010.

Chelsea didn’t play a 4-1-3-2 during the Lampard years, but his role was exactly that of the Diablo’s free-roaming central midfielder, instructed to join the forwards at any opportunity, usually with a goalscoring outcome.

Lampard’s scoring record, which may never get the recognition it deserves, actually seemed to verge on ‘cheating’. And in a career strewn with brilliant moments, one match typified Lampard’s absurd finishing ability better than most. You might remember it.

On March 12, 2008, Lampard scored four goals in a game against Derby, a match that shook our Sixth Form Fantasy League table to its foundations.

Four goals from central midfield. Just think about that for a minute. This might have been against the worst Premier League opposition of all time, and one might have been a penalty, but four goals for a central midfielder is genuine glitch-in-the-Matrix stuff.

If Diablo could be explained away as a ‘bug’, then what the hell was this?

Clearly, Lampard wasn’t cheating, which can mean only one thing: Diablo, the freak tactic with the seemingly impossible central midfielder, was real all along.

For whatever reasons — envy, bias, blindness — Lampard seems destined to be ranked slightly below peers like Steven Gerrard and Paul Scholes.

There’s nothing we can do about that, but Lampard’s commitment to justifying a computer game tactic should never be forgotten.

By Benedict O’Neill

READ NEXT: A celebration of Renford Rejects, one of the best kids shows of all time

TRY A QUIZ: Can you name every Chelsea player to score 20+ Premier League goals?